I, along with a couple of other teachers, are piloting a grading strategy that is generating some interesting conversations on a DAILY basis with our students!

We’ve all read that grades do not improve or motivate learning. In fact, once a grade is given, the student assumes that idea is ‘done’ and drops it, moving on to acquire the next grade.

What I am about to share with you has MY KIDS talking about how THEY can improve their learning…

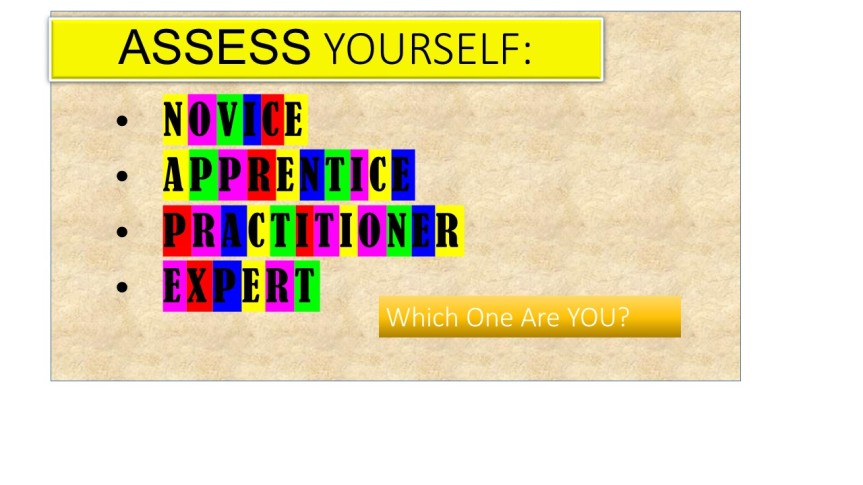

First, I have to give credit for the base of this idea to an amazing educator that I work with every day: Rebecca K. She, of course, credits it to an idea she learned in a workshop some years back. Anyway, she started the year off with a cool bulletin board, that looks something like the image above, which I used to create a powerful way to motivate my babies to take more responsibility for their own learning!

The students I am talking about are your average 9th grade (yes, FRESHMAN!!) students, that run the gamut of every freshman stereotype you’ve ever met. Really. (This includes students with personal learning plans and students whose first language is not English!) AND we’ve got them talking about growth – THEIR growth – as learners. When we hand back a paper, instead of the ‘crumple it up and put it in the bookbag or the trash’ mentality, the comments are varying forms of, “..tell me what these results mean!”

Here’s how it works:

Four numbers, four learner identities: 1. Novice, 2. Apprentice, 3. Practitioner, 4. Expert

Novice: I’m just starting to learn this and I don’t really understand it yet.

I explain to the students that this is where everybody in class starts out. Algebra I will have lots of things that are new to them, and we expect that they won’t be familiar with the material! We don’t expect them to know it all before we teach it. Sounds obvious, right? Sometimes you have to be explicit with Freshmen. I think that’s where the name originates!

Apprentice: I’m starting to get it, but I still need someone to coach me through it.

The apprentice is the beginning of the learning phase. When a student gets a 2 on a problem or a whole assignment, they are in the initial learning stages. As a teacher, I’ve just told them (by marking it a 2) that I know they still need help with the concept, and that I will be supporting their learning. This also tells them that they are not there YET – and that they have room to continue learning. Sometimes we have to give kids permission to not know things YET!

Practitioner: I can mostly do it myself, but I sometimes mess up or get stuck.

This is a proud moment for most of my students. That little 3 next to a problem or on a paper, tells them so much more than a traditional grade. This sends them the message that I get it that they’ve got it! This affirms their learning. This affirms their work. This is personal. Better than that, this motivates them to keep going, to keep learning. They ALL want to be….

Expert: I understand it well, and I could thoroughly teach it to someone else.

Isn’t this where we want our babies to be? You know that if they know it well enough to teach it – THEY KNOW IT!! That peer tutoring thing is for real! Please notice that there are TWO parts of this level: knowing and teaching.

How does this work?

My (totally awesome) co-teacher, Stephanie W., and I, use the following grading process. Feel free to modify it to fit your students, and what is happening in your classroom. We know that what we are doing is working for our kids – you may want to start with this, and then modify as you see what is working for you.

We give an assignment or quiz. We grade each problem with a 1, 2, 3, or 4. We add up all the grades and divide by the number of items. That gives us a number between 1 and 4. Many times that will generate a decimal, say 1.8 or 2.5, or even 3.8. Here is an important point: we DON’T ROUND UP! We DO EXPLAIN the process to our students. It is important for them to understand that this is not arbitrary. They must own the process for this to work. These conversations happen EVERY time we return an assignment. That’s a GOOD thing!

Our goal for our students is mastery, so unless the resulting average is an actual 2 for example, the child is still a NOVICE (1, 1.2, 1.8, 1.9 – doesn’t matter. They are still a 1). Same with 2 point anything – they are still a 2, same with 3 point whatever – still a 3. The ONLY exception is 3.8 and above. If the student has one or more 4+ answers, with clear justification statements, then, and only then, will we round up to a 4. See below for the PLUS explanation!

Our evaluation goes something like this:

a) Answer that is incorrect, No work shown, or No answer at all: give it a 1.

b) Answer with some work shown (they attempted a solution) but it is incorrect in major ways and answer is incorrect or incomplete; give it a 2 (remember they are still learning and need more help!)

c) Answer given is incorrect, but work is also shown. (OR answer is correct, but NO work shown to support the answer). Student did pretty good, but minor errors and/or mistakes caused the incorrect answer; give it a 3. This student is obviously getting it, but he/she is letting errors get in the way. Maybe they are lazy, maybe in a hurry. The 3 tells them that they are getting it – but they NEED TO BE MORE CAREFUL! (The 3 for NO work shown is to allow us to ensure students are not ‘borrowing’ answers from another student! We are giving them the benefit of the doubt until further notice.)

d) Answer and work is shown and is completely correct. This baby gets the 4! The student can feel the glow of being an expert. But wait, there’s more! This only satisfies HALF of the description. What about the ‘teaching’ part?

Four “+”? What is Four Plus???

‘Four +’ is that special designation for the child who not only knows the material, but can prove to us that they are able to teach the material to another student. Time dictates that we don’t have the opportunity for EVERY student to demonstrate teaching ability (although we do try to build in those opportunities!). We have explained to our students that the way to demonstrate this ability is to justify the work they’ve shown, with brief written explanations.

Written Justification sets the student up for PROOFS in Geometry

Algebra I is a class of foundations. It is important to teach with an eye to the future courses our kids will encounter, and proofs are some of the most difficult lessons for students. One of the Algebra I standards is to be able to justify the steps taken to solve simple one step equations. This is an important step to understanding that there is a mathematical reason for being ABLE to take that step – and not just because the teacher said so! By building this into the idea of EXPERT, we are modeling the concept that understanding – that is, the realization that there are solid REASONS for why math ‘works’ – is a valuable part of the learning process.

What WORDS do you use to tell a parent how their child is doing in your class?

I know this is just a brief overview of this process, but I wanted to share because I feel it is the first solid step in moving towards talking about GROWTH and LEARNING, instead of grades. I believe it is important that we take the focus off of grades, for students and parents. To do that, we, as teachers, have to stop using GRADES as the unit of measure in communicating with our students and parents. Unfortunately, our grading systems, and I’m talking the actual computer systems we have to use, are not set up to show mastery – they are set up to show GRADES!

I already changed my conversations, my wording, my language, with my students. It will happen with my conversations with parents in my next phone call/email home, as well. Will YOU?

What’s the downside?

My school still uses a grading system built on averaging traditional grading numbers. That means I can’t just put in 1, 2, 3, 4, or 4+. I have to turn these numbers into a grade between 0 and 100 that will accurately translate and describe my students’ mastery of the curriculum.

My solution is two-fold. The grades in my gradebook are tied to one of the required standards, and each of the above levels is tied to a number that has already been given meaning by how it is used as a grade. While the first is fairly easy to accomplish, the second is based on how parents and students interpret grades. A 100, for example is the ideal. That sends the message that the student has mastery of the assignment, or the course. In fact, anything above 93, in my County school system, is an A, and as such, denotes pretty much the same thing as a 100. Same for a B, or a grade in the 80 range. Those two grades are obviously acceptable to most parents and students. The grade of C is a little more ambiguous. The C denotes that the student is somehow less than perfect, but still passing. While a student may be GLAD to have a C – it does denote that the student is doing the work and IS mastering the concept – it doesn’t have the same cache’ as the A and B grades.

So how do I reconcile the grades with the numbers?

A novice receives a grade of 65. The Apprentice receives a 70. The Practitioner has earned an 80, and the Expert, a 90. The 4+ student will earn a 100, as long as all problems on the assignment or quiz show justification, evidence that they have not only mastered the concepts, but have gone above and beyond to be able to communicate their knowledge with others.

The final issue I will address here: What happens when a student makes no effort at all. Our students never do that, do they??? In that instance, the student has given us no information on which to base a grade. Effectively, they have NOT TURNED ANYTHING IN. The grade in the book becomes an NTI, and we are made aware that we need to step up our efforts with that student. An NTI is a zero, until the student completes an assignment on that material, and we can assess mastery. From there, the averaging work of the gradebook takes over, and the grade reflects the whole course mastery. Grades in this context are fluid, and can be changed by future mastery as evidenced by quizzes or testing situations.

The system is not perfect, but the teachers with whom this is working believe that we have created a system that truly tells us where our kids are with the curriculum, and allows us to modify our teaching darn near immediately, so that we can address the areas in which they need further help – which is the actual point of all this grading, isn’t it?

Here is the poster we use in our classroom to explain the levels. Our students get their own mini copy for their notebooks. We utilize a small chart of “I can” statements for each unit – no more than 3 – 5 statements – that allow the students to chart their progress. Here is the chart for our Unit 1 standards. The kids get this, too. You can use any “I can” statements you need for your particular units.

At the beginning of each unit, the STUDENTS determine their pre-assess level, the quizzes give them the mid-assess levels, and then the unit tests are the post-assess level. The students keep track of these themselves. We incorporate a running conversation DAILY of what their goals are, where they think they are with these goals, and how they are going to get to the 3 and 4 levels. I have personally found this is a great way to have the students tell me where they are at the end of instructional and practice periods throughout class. I simply ask them where they think they are – 1, 2, 3 or 4. The majority of students are incredibly honest, because we are all speaking the same language. The ability to quickly assess and modify my teaching is been made incredibly easy! Grading has become a process of assessing growth, not despairing over what they don’t know. I LOOK FORWARD to grading the work, knowing most of my students WANT to have a conversation about where they are, and what they need to do to get to the next level. Let me know if you would like the rest of the “I can” levels we are using with this course. I’ll be glad to share!