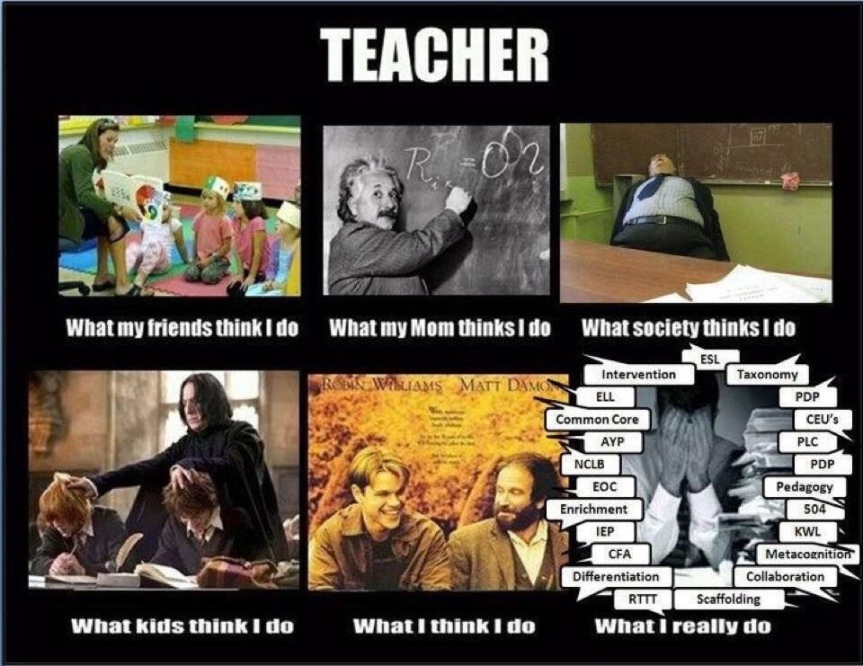

We question our students to elicit and engage, to push their sensemaking, to activate prior knowledge, and to get them thinking about their thinking. But do we question ourselves and our pedagogy with the same focus?

Table taken from National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. (2014). Principles to actions: Ensuring mathematical success for all.

In the rush to use new ideas, incorporate technology, or just ensure our students are doing math things from the minute they walk through the door, are we giving enough thought to why we are choosing an activity? What is that activity suppose to achieve? Has it earned the time it will take, not only for the students to complete, but for the grading and feedback? In other words, will it move these students further towards the goal?

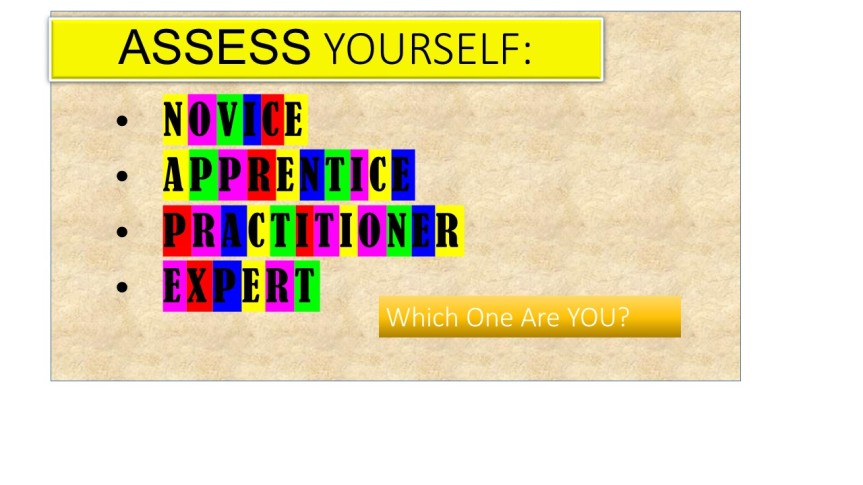

Learning Targets are Not Just For Kids

My colleagues and I have been asked to share learning targets with our students; to write the daily lesson or goal on the board and go over it, so students know what successful learning looks like.

As you think about what your students will be doing, do you ask yourself just how the activity will provide the experience you want for the student? What will it tell you or your student about their learning? How will it move them closer to understanding? How will it engage the learner to produce the desired result? What will the failure of this activity tell you? Tell your student?

For the math classroom, skill builds upon skill. Knowledge is formed by understanding how the old can be reshaped or used to fit into the new. It’s like reading, but with numbers. In learning to read, we begin to decode shapes that are letters, that make sounds, that can be arranged into words (patterns of letters), that are then arranged into larger groups of sentences to convey information.

In mathematics, we learn our numbers, which instead of sounds convey amounts. At first, these amounts are concrete, as we count fingers or toes or toys or blocks or cheerios. At some point the numbers begin to represent the amount. We put these numbers together into groups that define patterns, and we put these patterns into sentences that convey information. Every time we learn a new concept, we can place that building block in context and do more than we could. A concept in math means we’ve identified a relationship, a cause and effect, a reasoning about how one action effects an outcome. When we understand the connection, we can extrapolate, interpret, compare, contrast, synthesize, and create. All of those things that we say we want our students to be able to do, no matter the subject.

Is this what your materials and lessons are teaching?

Every teacher reading this has bemoaned the lack of time we have in the classroom. How we spend that time often forces us to cut our activities, explorations, and conversations about the material. We have to hit the ‘most important’ standards, or the ‘big ideas’. Yet we know that knowledge is built by exploration, by focusing on a problem or situation, by playing with ideas. But how often have you asked ‘how will this activity increase understanding of the concept?’ ‘What is it teaching?’ ‘How does it allow showing the learning, or mastery?’ ‘Will it allow for connections to what has already been done, or to what is to come?

Is the idea or activity sticky?

By sticky I mean will this be something the student will think about longer than the activity itself. Will a student come in a day or a week or a month later and say, ‘I’ve been puzzling about this idea and I think I finally get it.’ And yes… I believe all of our ideas can be sticky – not necessarily for everybody at the same time. If we are truly giving each part and moment of our lesson thoughtful care, there will be more sticky moments than not. Those moments are what build interest, knowledge, and understanding. One of the best examples of this is the Four Fours activity. My students worked on that for over a week!

How do we get there?

1. Put yourself in your students’ shoes.

Think about what is happening to them daily. When they walk into your class, where are they coming from? Have they had time to process their last class? (Probably not.) Are they looking forward to math or dreading it? Did they do their homework – or even understand it? Is your class a relief, a chore, or an interesting, thought provoking space in their day? As I write this, I see the faces of my students, and can easily see the few that truly look forward to this class – but there are occasions where my lessons have let them down, too!

What do they need from you in that moment, to get their mind off of what has happened up to the moment they walk through your door?

For a start, pretend you are a student and walk into your classroom. Pick up that starter. Take it to a desk and try your own lesson. Where is your student brain? How does it make you feel? Does it do you want it to do? Loosen them up? Assess yesterday’s lesson? Review a skill they need in the main lesson? How will you check the outcome? This shouldn’t be a ‘take up and grade’ – it’s very name implies short, sweet, and to the point. What you want to accomplish must guide what you do. What you do sets the tone for the rest of the class. If the starter isn’t working for you, it isn’t working for them. Stop. Just stop doing what doesn’t work.

One teacher I know

has a great routine. She has trained the kids to pick up a starter (half page, every day) on their way in. Some fill it out. Some don’t. She goes over each problem, quickly working it on the board. She asks a few questions about the numbers or the process. Usually she has to get the class’ attention, many are off task. The kids who knew how to do this are already zoned out. The ones who don’t know how either copy her work down exactly, or don’t write anything. She does this quickly, and in her mind this is circling back around as a review for weak skills or concepts. She is practicing good classroom management by getting kids in their seats and working. She has trained them that math is boring.

During one week, she gave the same material as a starter and as a quiz to check for Learning. To her frustration, it did not result in increased knowledge for those who hadn’t already learned it (and I suspect it was extremely boring for the handful who did!) This is a 15-20 minute activity every day. How could she change this activity to get the desired outcome, i.e. strengthening this skill?

2. Ask yourself what your lesson is teaching: Process or Concept?

A process is a pattern of activity. A concept is the explanation or reasoning for why we do the process. Teaching a concept should lead to the process. In the interest of time, students often learn the process. Then it’s practice, homework, and a test. Are you teaching process or concept? Are you reviewing process or concept? Are you practicing process or concept? Concept is harder, takes more time and doesn’t work well on a worksheet. It is much more interesting, however. Concept is sticky.

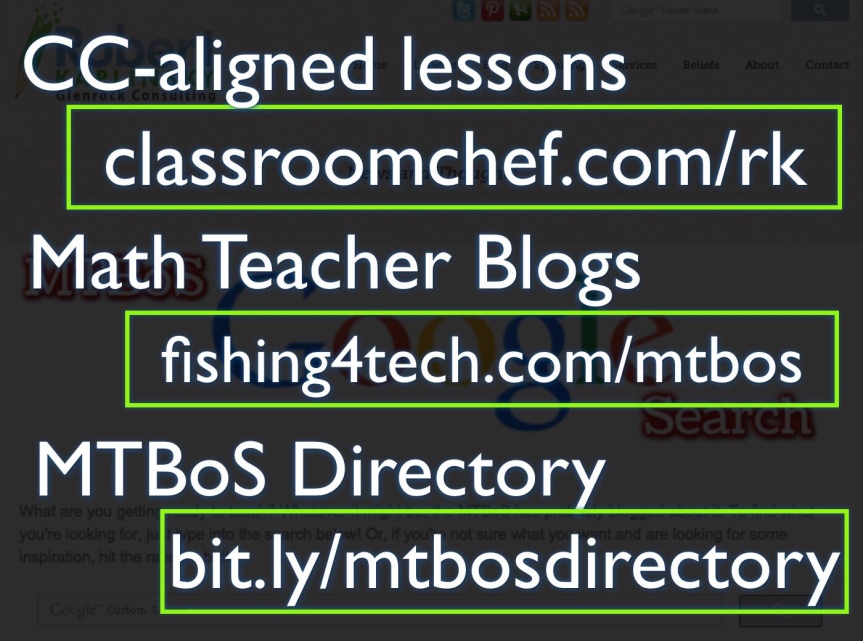

You do not have to reinvent the wheel!

No time to write those magnificent lessons? Have I got a tip for you! You do not have to do this alone! Lessons and resources are out there and so many are FREE. Check out these links (courtesy of Matt Vaudrey and the #MTBoS:

Not only will you find good lessons, you will find teachers who are constantly looking for better ways to share this wonderful world of mathematics!

Here are a few more questions for you to consider, (and which I will be grappling with while planning my next classes):

3. What is my lesson intended to do? How do my materials (problem set, delivery, class activity and structure, timeframe, sensemaking, etc) support this goal?

4. Where are my kids likely to fail? What can I do beforehand to support the weak spots (Starter idea!)?

5. What does the learning of the concept look like? What do I do for those that ‘get it?’ What do I do for those that need more? How will I know (formative assessment). If they don’t start, WHY not? If they don’t finish, WHY not? Do they really know how to do it? Is homework appropriate- i.e. will this truly extend the learning?

6. Does my lesson connect this idea to what they already know? Does it give them a peek into a future idea?

7. When/how will I give them time to process what they’ve done?

8. When will I revisit? How will I revisit? (Yes! Plan for this!)

I leave you with this:

The moment you can really know a student has internalized a concept/learning target is the moment you hear/see them sharing what they’ve learned with another student. Plan for that, too.